Iban Pua

Woven cotton, natural pigment dyes; 205 x 109 cm. Purchased by Sally Nelson from creator, $50. | Woven cotton, natural pigment dyes; 201 x 72 cm.

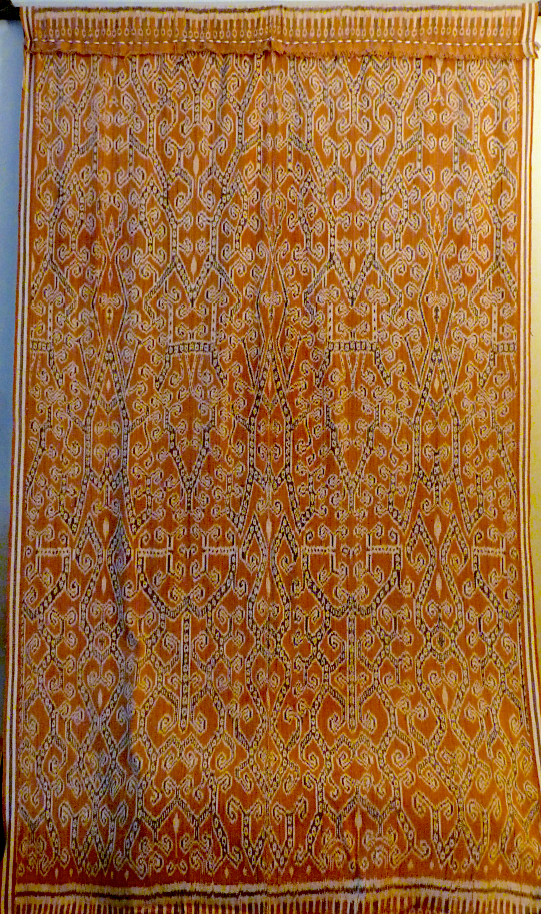

The source of the designs, motifs and materials for Iban pua, or warpikat ceremonial weavings, is the natural environment of central Borneo, which is also the context from which beliefs about the temporal and divine worlds derive. Animal, botanical, human and spirit forms, and geometric patterns are common themes as are simpler border decorations.

The difficulty in obtaining the brick red dye which is used in all puas and the skill required to make a warp ikat imply great ability on the part of the women who make these items. For example, the weaver must gather and process the herbs necessary to process cotton before beginning a pua, and mordanting (the treatment of cotton for color-fastness) is itself a complex chemical process taking years to master. Iban men are judged on their prowess in hunting expeditions; similarly, women are recognized for their weaving skills; to the extent that together all the elements of pua making have been called "the women's war."

Cloth in general is intimately related to Iban beliefs and myths. Pua, for example, play a fundamental role in ceremonies, and are hung to mark out the ritual area. The ritual importance and spectacular nature of Iban textiles have attracted the interest of collectors since the early nineteenth century, and since then there have been many different interpretations of the meaning and significance of pua and their patterns.

The pua is used for the many rituals of a person's life from birth to death: to wrap a baby for the ceremony of its first bath and at death to screen a corpse when it is laid out in state on the verandah before burial. The latter is an example of the way the pua can be used to define ritual space, or a sacred area, forming a boundary between the realm of the mortal and that of the spiritual or supernatural. A pua can mediate between man and the spirit world, and for this reason, the cloth has spiritual power woven into it with its design.

Puas are produced using the exacting ikat technique, a meticulous backstrap loom process that involves tying and dyeing the intricate and colorful patterns into the threads before they are loomed and woven. In contrast to many other peoples of Borneo and elsewhere in island Southeast Asia who recognise hereditary hierarchies, the Iban social structure is fundamentally egalitarian, and a person's social status should theoretically be dictated by individual achievement. While a man could until the mid-twentieth century achieve status through his prowess as a warrior and taker of heads, a woman's status was, and in many cases still is, determined by her skill as a designer and weaver of puas.

Formerly, a man should ideally have taken a head prior to marriage, and a woman should have woven a pua. Treating the cloth to make it absorb the rich red dye fundamental to Iban textiles, as so well displayed in the pua on this page, was referred to as "the women's warpath," which could also refer to the entire pua-making process. Like going to war, weaving was a potentially dangerous and even life-threatening practice. The patterns of pua were understood as being powerful supernatural elements, and the various motifs could be ranked according to their power. Whether established or new, all patterns were said to be revealed in dreams in which the weaver would be visited by ancestral women who would teach her the intricate designs. A novice weaver would begin with the simplest motifs and only very gradually work towards the more complex and powerful, which if improperly executed could weaken her vital force, eventually killing her.

A beginning weaver invariably starts by weaving a simple design on a small piece of cloth. She is only allowed to start weaving a piece that is fifty kayu wide (a kayu refers to groups of three single threads in the warp). By the time she is ready to weave her tenth pua, she will be weaving a piece that is a hundred and nine kayu in width. These restrictions are rigidly adhered to, as they are of ritual as well as practical importance.

Once a woman is recognized as being adept she is considered accomplished. She can weave basic patterns, but is unable to invent her own, depending instead on the designs of her mother and grandmother. If she needs or wishes to widen her repertoire, she has to make a ritual payment to obtain a design from a more proficient weaver. If the master weaver does not possess the required design, she might obtain it from someone of the next skill level down, the indu nenkebang.

A woman of this status can invent her own designs, inspired by the supernatural elements in her dreams. She is an extremely proficient weaver, and will have the power to attempt potentially dangerous patterns. She is widely respected by the community and wears a porcupine quill tied with red thread as a mark of distinction. She is likely to be quite wealthy, as she is paid well by other weavers for her designs.

Woven cotton, natural pigment dyes; 237 x 104cm.

A woman can only reach this position if she is able to judge the correct quantities for the fixing solution and the dyeing solution. She is primarily a chemist, adept at completing the exacting dyeing process successfully through the application of fixative and natural dyes, which prior to the arrival of imported commercial threads and chemical dyes was the sole choice of colorant. Although the fixative ingredients are common knowledge, the completion of the process (the actual application of the fixative to the raw cotton) is a challenging ritual process, as without spiritual intervention the desired color cannot not be attained. To achieve status as a member of this respected class a woman is required to excel in all areas of knowledge, skill and behavior. In addition, she must win the approval of the spirits in the metaphysical world who will appear to he in dreams to bestow their acceptance and consent in recognition of her prowess. Though it is probable that a woman of this position would come from an ancestral line of weavers, it is also possible for an exceptional woman to work her way up to the position of master weaver. Considerable courage and daring are required to overcome the fear of transgressing ritual prohibitions.

The motifs and patterns on each pua represent meanings which have resulted in varied interpretations by anthropologists and collectors. An attempt to individualize and interpret every single design or represented symbol in a given piece often distorts the intended meaning of the piece as a whole, and there is considerable danger of mis- or overinterpretation. The interpretation of the total significance of the design lies in the combination of the symbols and the general layout of the piece.

A detailed description of the appearance of motifs alone thus has little meaning and falls short of encompassing why a pua is designed a particular way. It is important to consider factors such as the purpose for which the pua has been woven, its date and historical context, and the life story of the weaver herself, as well as to be aware at least of the existence of the rich repertoire of allusions to Iban legend, religion and oral history. The pua kumbu is essentially a narrative, which may tell a mythological story or a personal tale or represent a historical archive.

Despite the rich archive of pua motifs and combinations, innovation is also highly prized by weavers and community alike. Consequently, one of the chief hallmarks of an excellent pua is the quality of creativity and ingenuity. Pua motifs were not simply passed down unaltered through the generations - some motifs may actually be the trademark of an individual weaver, and she can pass those down to her heirs. In a few cases, some particularly powerful antique puas have been copied for learning purposes and to preserve their designs. In general, however, rather than simply copying designs from existing puas, a weaver will attempt to find new ways to put her unique interpretations and expressions into each piece. The Iban have a immense archive of oral literature, and these stories form the inspiration for motifs and designs. A virtuoso weaver would weave her own experience and dreams into established stories derived from the canon. By demonstrating her skill in manipulating stories and metaphors from the canon, in combination with details from her personal life, the weaver expresses her personality, including her ambitions and her anxieties into each cloth she composes.

This is not to say that any weaver may use any design she likes in composing a cloth. Relatively safe designs depict jungle vegetation, like vines, creepers, trees and bamboo. They were historically the first motifs a novice weaver made. Potent and dangerous designs depicted human, demon and animal totem figures, like crocodiles and serpents. The humanlike figures are called engkaramba. Some motifs, like centipedes, form a protective barrier. They keep malevolent and powerful motifs within the enclosure of the barrier. This enclosure prevents their power from spilling over the barriers on the cloth and in turn harming the weaver and her family. Traditionally, puas depicting human or supernatural figures were made only once a weaver had achieved a high status. Today, however, because these designs are in greater demand by collectors, the previous taboos are not as strictly adhered to. Consequently, puas with these figures are now more common.

In recent decades, ritual and supernatural uses for pua such as headhunting and shamanism have diminished, but the cloth continues to be made, carrying different meanings and purpose. For example, some Iban have begun using the cloth to mark a distinct indigenous identity separate from the Malay majority. The cloth signals a personal and cultural connection to the history of Sarawak. The pua kumbu, which cis an international art commodity, now also demonstrates wealth, taste and refinement both domestically and abroad. Some weavers are now able to earn an income from selling their artwork overseas. For these women, the cloth can bring fame, status, and the ability to participate in a global market that would otherwise be closed to them.

Nelson South East Asia Collection © 2025